Here’s what’s happening around the world in the area of child welfare and protection.

Photo courtesy of CTWWC

Children thrive in safe, nurturing families. However, children are sometimes separated from their families, which may profoundly affect their development and expose them to exploitation and violence[1]. The system to care for children can be assessed and strengthened to deliver services to support children and families. For example, standards can help make sure services are appropriate and effective, and policies can lead to more government resources to deliver such services, whilst monitoring and evaluation systems can help decision makers be more evidence-driven.

Care System Assessment

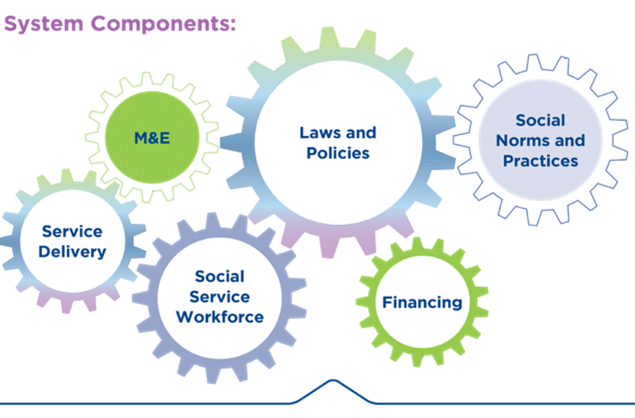

In 2017 a global health and social service project called MEASURE Evaluation developed a care system assessment tool [2], and conducted care system assessments in Armenia [3], Ghana [4], Moldova [5] and Uganda [6]. The assessment was designed to assess laws and policies, the social service workforce, service standards, monitoring and evaluation, social norms and financing related to alternative care. In 2019, Maestral, through a global initiative working on children’s care called Changing the Way We Care (CTWWC), adapted the MEASURE tool and developed a training package [7] and conducted assessments in Guatemala[8] and Kenya [9]. In 2022, Data for Impact (D4I), a continuation of MEASURE Evaluation, and Changing the Way We Care joined together to learn about how well these assessments were conducted, how the assessments contributed to change, and what could be improved for other countries to assess their care systems in the future.

In 2017 a global health and social service project called MEASURE Evaluation developed a care system assessment tool [2], and conducted care system assessments in Armenia [3], Ghana [4], Moldova [5] and Uganda [6]. The assessment was designed to assess laws and policies, the social service workforce, service standards, monitoring and evaluation, social norms and financing related to alternative care. In 2019, Maestral, through a global initiative working on children’s care called Changing the Way We Care (CTWWC), adapted the MEASURE tool and developed a training package [7] and conducted assessments in Guatemala[8] and Kenya [9]. In 2022, Data for Impact (D4I), a continuation of MEASURE Evaluation, and Changing the Way We Care joined together to learn about how well these assessments were conducted, how the assessments contributed to change, and what could be improved for other countries to assess their care systems in the future.

What we’ve learned

In 2022, CTWWC and D4I interviewed 14 people[10] who participated in the assessments and/or used the results: four people each from Armenia, Kenya and Guatemala; and two from Uganda. Based on these interviews, learnings were deduced to help conduct future assessments and improve care systems.

Participating in the assessment improves knowledge and capacity, and increases collaboration among critical actors. Most of the respondents who participated in the assessment shared positive experiences. Actors gained knowledge about the care system – both the current system and best practices to improve it. There was value in simply bringing everyone together to learn, discuss and build consensus on ways to improve children’s care through system reform.

“First, I would like to say that this process helped me, as a healthcare professional, better understand child protection system, go deeper into those issues.” (Armenia, government actor)

Assessing the system has led to improvements in care systems. Care systems have improved based on the use of assessment results. Most commonly, national laws, policies and strategies have been developed or revised. The assessment informing the National Care Reform Strategy in Kenya, service referrals (Armenia) and the development of foster care guidelines (Uganda) are examples. The care system assessments directly contributed to these foundational national documents, which, in turn, help guide the way the care systems are designed to care for children and families.

“For the first time during the assessment we start talking about the system holistically from A to Z.” (Armenia, government actor)

Involving different actors, many of whom have different perspectives and knowledge of caring for children, is beneficial. The assessment created connections and relationships that are important for working together across sectors. Before the assessment, some actors did not necessarily see themselves as part of the care system, nor understood their role in the system. The assessment helped them realize their roles and how they fit into the care system.

Improving the way the system works takes a lot of time and resources. The assessed care systems are nascent and need substantial improvements. Reforming these systems is a complex, long-term goal that will take years, if not decades. The changes that have occurred are important and demonstrate progress yet are small parts relative to what is needed to fully reform a system. While incremental progress is good, seeing comprehensive and large-scale change is going to take a lot more time and resources.

Active participation in and political commitment to change is important. A factor in the assessment results leading to change is participation and political will. Countries that formed multi-sectoral teams to oversee, guide and participate in the assessment had political support for the assessment.

Staff turnover puts the momentum and priorities identified during the assessment at risk. In all sampled countries, government personnel changed after the assessment. The changes of government seems to have affected system progression and priorities. New government staff seem to be less aware of the assessment, and the detailed findings, despite the availability of assessment reports. Orienting new government staff in the full assessment and findings has not been common practice.

Conclusions

– To be effective, there should be a core-team guiding the assessment that is drawn from different government agencies responsible for caring for children. Including non-governmental actors and people who have experience in the care system (e.g. care leavers[11]) on this team is also a good practice and is highly recommended.

– The importance of government giving this team the official mandate and authority to make sure the assessment is completed with a high degree of quality is vital.

– Gathering relevant actors to conduct the assessment together creates value that will last after the assessment is done. It also leads to better coordination and collaboration.

– Do not assume that all actors have the same understanding of and vision for the care system. It is important to consider who is involved and ways to improve knowledge of what a care system is.

– Because the assessment is likely to identify more areas for improvement than a country can resolve in the near term, it is important to determine how to prioritize recommendations.

– Before conducting the assessment, define how the results will be used – for a national strategy, an annual work plan, a national policy, or something else. How the results will be used can guide the timing of the assessment as well as which recommendations are prioritized.

– Staff turnover is inevitable, and governments will change. Plan for this. Consider this in both determining the timing of the assessment and consider developing assessment dissemination and communications plans.

– An external facilitator is helpful in designing and implementing the assessment to help overcome some of the challenges described above.

[1] UNICEF. Changing the Way We Care. An Introduction to Care Reform. 2022. Retrieved from: https://bettercarenetwork.org/sites/default/files/2022-10/introduction_to_care_reform.pdf

[2] https://www.measureevaluation.org/resources/publications/tl-19-25.html

[3] https://www.measureevaluation.org/resources/publications/tr-18-268.html

[4] https://www.measureevaluation.org/resources/publications/tr-18-251.html

[5] https://www.measureevaluation.org/resources/publications/tr-18-262a.html

[6] https://www.measureevaluation.org/resources/publications/tr-18-250.html

[7] https://bettercarenetwork.org/toolkit/individual-assessments-care-planning-and-family-reunification/assessment-forms-and-guidance/care-system-assessment-framework

[8] Guatemala’s assessment report was developed and kept internal to government and partners.

[9] https://bettercarenetwork.org/library/social-welfare-systems/child-care-and-protection-policies/kenya-national-care-system-assessment-a-participatory-self-assessment-of-the-formal-care-system-of

[10] 14 people (4 from Armenia, 4 from Guatemala, 4 from Kenya and 2 from Uganda) were interviewed using a semi-structured questionnaire. 13 of the 14 participated in the system assessment in their country. One (in Guatemala) joined his position when the assessment was being finalized. 10 of the 14 respondents are government staff, 2 are from civil society and 2 are from other non-governmental organizations (i.e., UNICEF and an Association of Social Workers).

[11] Careleavers are people who have had experience in the care system, often describing people who lived in institutions or were placed in alternative care as children, as well as the caregivers of these children.